WHO (GA)

-

Dear Delegates,

Welcome to the World Health Organization (WHO) General Assembly! My name is Natalie Yoo, and I am looking forward to serving as your chair for this year’s CESIMS committee. I’m currently a sophomore at Barnard College studying Mathematical Economics and hoping to pursue a minor in Architecture. During my time here, I’ve had the chance to explore the intersection of economic strategy, policy research, and international relations, which has deepened my appreciation for how global cooperation and evidence-based policymaking drive public health progress.

In this committee, we’ll be diving into two of the most critical questions facing WHO today: how to make Universal Health Coverage a lived reality, and how the regulate Artificial Intelligence in Health Systems responsibly and ethically. Both topics push us to think beyond simple policy statements – to question implementation, equity, and accountability on a global scale. My hope is that our sessions challenge you to approach these debates not only as policymakers, but as problem-solvers who recognize the humanity behind the statistics. Whether this is your first Model UN conference or your fiftieth, you’ll find that the most rewarding part of committee isn’t just crafting resolutions – it’s building ideas together that feel purposeful and innovative.

I can’t wait to see the creativity and insight each of you brings to the table. I hope that this committee is one that reflects the best of diplomacy: empathy, intellect, and the shared pursuit of better health for all.

Best regards, and excited to meet soon,

Natalie Yoo | nyy2006@barnard.edu

-

Code of Conduct

All delegates will be held to a high standard of behavior and will be expected to treat each other and the topics of debate with respect. No harassment or bullying of any kind will be tolerated. Sensitive discussion of topics is expected to be conducted respectfully and intelligently. The Secretary-General of CESIMS reserves the right to remove a delegate from the conference at any point in time.

Attire

All delegates will be expected to wear Western Business Attire.

Language

The working and official language of the committee shall be English.

Parliamentary Procedure

Points

There are four types of points that a delegate may raise.

Point of Order

A Point of Order may not interrupt a speaker and can be raised when the delegate believes the rules of procedure have been violated. The chair will stop the proceedings of the committee and ask the delegate to provide warranted arguments as to which rules of procedure have been violated.

Point of Personal Privilege

A Point of Personal Privilege may be raised when a delegate’s ability to participate in debate is impaired for any physical or logistical reason (for instance, if the speaker is not audible). This point may interrupt a speech, and the dais will immediately try to resolve the difficulty.

Point of Parliamentary Inquiry

This point may be raised by a delegate who wishes to clarify any rule of procedure with the Chair. It may not interrupt a speaker, and a delegate rising to this point may not make any substantive statements or arguments.

Point of Information

As the name suggests, this point may be raised by a delegate to bring substantive information to the notice. It may not interrupt a speaker and must contain only a statement of some new fact that may have relevance to debate. Arguments and analyses may not be made by delegates rising to this point. A point of information may also be used to ask questions of a speaker on the general speakers list.

Motions

Motions control the flow of debate. A delegate may raise a motion when the chair opens the floor for points or motions. Motions require a vote to pass. Procedural motions, unless mentioned otherwise, require a simple majority to pass.

Motion for Moderated Caucus

This motion begins a moderated caucus and must specify the topic, the time per speaker, and the total time for the proposed caucus.

Motion for an Unmoderated Caucus

This motion moves the committee into unmoderated caucus, during which lobbying and drafting of resolutions may take place. It must specify the duration of the caucus.

Motion to Suspend Debate

This motion suspends debate for a stipulated amount of time.

Motion to Adjourn

This motion brings the committee’s deliberation to an end, and it is only admissible when suggested by the Chair.

Motion to Introduce Documents

A successful motion to introduce essentially puts the document on the floor to be debated by the committee. The sponsor of the document will be asked to read the document and then, if deemed appropriate, the Chair will entertain a moderated caucus on the topic.

Motion to Divide the Question

This motion may be moved by a delegate to split a document into its component clauses for the purpose of voting. This may be done when a delegate feels that there is significant support for some clauses of the document, but not for the complete document.

Motion for a Roll Call Vote

A delegate may move to have the vote conducted in alphabetical order.

Motion for Speakers For and Against

If it would help the proceedings of the committee, a delegate may motion for speakers for and against a document.

Documents

Committee Documents represent the product of the committee’s deliberations and their collective decisions.

Directives

Directives are similar to resolutions in traditional committees, with the notable exception that they do not include preambulatory clauses and are much shorter and more concise. Directives are generally written in response to a specific crisis update, and can be as short as two or three clauses. All direct actions by the committee as a whole require a directive.

Communiqués

Communiqués are formal communications (private by default) directed from the committee to other governments, individuals, or organizations. Committee communiqués pass by simple majority.

Press Release

Press releases express the sentiments of the committee (NOT individuals) on any issue. They require a simple majority to pass.

Amendments

After the first draft of a committee document has been introduced, delegates may move to amend clauses of the draft. If the amendment is supported by all the sponsors of the documents, it passes as a friendly amendment.

Communication During Committee

Communication during committee may take place through handwritten notes:

Notes Between Delegates

Delegates should feel free to write personal notes to their fellow committee members. We ask that these notes pertain to the business of the committee.

Notes to the Dais

Delegates may also write to the Chair with questions regarding procedural issues of the committee, as well as a wide range of personal inquiries. Delegates should feel free to write to the Chair on any issue that would improve the committee experience. This could range from a clarification of procedural issues to substantive matters.

Crisis Notes

Crisis notes are notes written in character to fictional confidants. Backroom staffers will respond to these notes in character. The success of your notes depends on how well the notes are written and researched, and how reasonable the request is.

-

I. Introduction

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) stands at the core of the World Health Organization’s mandate and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), representing the global commitment that all people, everywhere, should have access to quality, essential health services without suffering financial hardship. Despite decades of policy commitments and international declarations, achieving UHC remains one of the most persistent and politically complex challenges in global health. While 90% of countries have formally endorsed UHC in national policy, only a fraction have translated these commitments into equitable, functioning systems that reach all segments of the population.

At its heart, UHC is both a technical and moral imperative: a promise of social protection, equity, and human dignity. Yet, the persistent disconnect between policy ambition and practical implementation continues to undermine progress. Disparities in financing, infrastructure, workforce distribution, and governance leave millions without reliable access to healthcare. The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed these gaps – revealing that even well-resourced health systems are vulnerable without resilient primary care and financial protection mechanisms.

As delegates convene in the committee, they are tasked with addressing one of the most fundamental questions in health policy: how can nations transform the rhetoric of universal access into reality?

Bridging this gap requires confronting structural inefficiencies, re-evaluating financing models, strengthening health workforces, and building sustainable systems that are both resilient and inclusive.

II. Historical Context

The concept of Universal Health Coverage can be traced back to the founding principles of the WHO in 1948, which enshrined health as a fundamental human right. In the decades that followed, UHC evolved from a moral aspiration into a measurable global goal. The 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care first articulated the vision of “Health for All,” emphasizing community-based care and health equity. However, the momentum faltered in the 1980s and 1990s, when structural adjustment programs and reduced public spending on health in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) led to fragmentation and the rise of user fees (premiums).

A major shift occurred in the early 2000s, as global health financing mechanisms – such as the Global Fund, Gavi, and other vertical disease programs – began channeling significant resources into specific health areas. While these initiatives saved millions of lives, they also highlighted the limitations of fragmented, disease-specific approaches. Policymakers increasingly recognized that without integrated, system-wide investment, national health systems would remain fragile and inequitable.

The 2010 World Health Report, Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage, formally defined UHC around three pillars: (1) service coverage, (2) population coverage, and (3) financial protection. This framework guided the 2012 UN General Assembly Resolution on UHC, followed by its inclusion as Target 3.8 under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3) in 2015: “Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services, and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.”

The 2019 UN High-Level Meeting on UHC reaffirmed this global consensus, urging countries to “move together to build a healthier world.” Despite these policy milestones, progress has been uneven.

According to the WHO and the World Bank’s 2023 monitoring report, roughly half of the global population still lacks access to essential health services, and about two billion people face catastrophic or impoverishing health expenditures. This persistent disparity reveals the critical need to translate high-level commitments into operational, context-specific reforms.

III. Current Challenges

The global pursuit of Universal Health Coverage is hindered by a constellation of structural, financial, and political challenges that vary across contexts but share common roots. The gap between aspiration and implementation persists because many countries struggle to build resilient, equitable systems that can deliver quality care across all regions and populations. The following challenges illustrate the multidimensional barriers that impede meaningful progress:

Insufficient and Unequal Health Financing: Many low- and middle-income countries spend less than the recommended 5% of GDP on health. Reliance on out-of-pocket payments exposes vulnerable populations to catastrophic costs and deters care-seeking behavior. Donor dependence also creates volatility, as external funds often prioritize specific diseases rather than long-term system strengthening.

Workforce Shortages and Distribution Inequities: WHO estimates a projected global shortage of 10 million health workers by 2030, primarily concentrated in LMICs. Rural and marginalized communities are disproportionately underserved, exacerbating urban-rural health disparities.

Weak Primary Health Care (PHC) Systems: Despite global consensus that PHC is the foundation of UHC, many systems remain overly hospital-centric, underfunded, or fragmented. Weak PHC limits continuity of care, prevention, and early diagnosis, leading to higher system costs.

Fragmented Governance and Coordination: Overlapping ministries, donor-driven programs, and poor intersectoral coordination often lead to inefficiencies and duplication. Inconsistent leadership or political instability further impedes long-term reforms.

Inequitable Access and Social Determinants: Disparities in income, education, gender, geography, and minority status remain major determinants of health outcomes. Marginalized populations – including refugees, indigenous communities, and informal workers – often fall outside insurance schemes.

Data Gaps and Weak Monitoring: Many countries lack robust data systems to track coverage, quality, and equity. Without reliable health information systems, policymakers cannot effectively target reforms or allocate resources.

Resilience and Emergency Preparedness: The COVID-19 pandemic revealed deep vulnerabilities in health systems worldwide, showing how easily service continuity, workforce safety, and financing mechanisms can collapse under crisis pressure.

Collectively, these challenges underscore that achieving UHC is not only a question of political will but of system design, sustainable financing, and governance reform. While the principles of UHC are universally endorsed, their realization depends on aligning resources, accountability, and political commitment toward inclusive, resilient, and people-centered health systems.

IV. Current Solutions & UN Resolutions

In response to these challenges, WHO and its Member States have developed a range of policies, frameworks, and cooperative mechanisms to transform UHC from policy into practice. These initiatives aim to strengthen primary health care, secure sustainable financing, and institutionalize accountability for equitable access:

WHO’s Framework for Action on UHC (2010 – Present): WHO’s operational guidance emphasizes three irrelated strategies – expanding service coverage, reducing out-of-pocket spending, and improving service quality. Member States are encouraged to adapt these principles through context-specific reforms that prioritize the most vulnerable populations.

The Astana Declaration on Primary Health Care (2018): Building on Alma-Ata, the Astana Declaration reaffirmed PHC as the cornerstone of UHC, calling for integrated, community-based approaches that link prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation.

Global Monitoring Reports on UHC (WHO & World Bank): Regular assessments provide data-driven insights on coverage indicators, financial protection, and policy implementation gaps. The 2023 report urged nations to “course-correct” by investing in equitable financing and stronger PHC systems.

Sustainable Health Financing Initiatives: Programs such as the WHO Health Financing Progress Matrix and the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-Being for All promote domestic resource mobilization and efficiency in public spending

Partnerships and Multisectoral Collaboration: WHO, the World Bank, and other partners support the development of UHC compacts – country-led strategies aligning donor funding and national priorities under a shared accountability framework

Digital Health and Innovation: Emerging technologies – including telemedicine, electronic health records, and AI-supported logistics – are being leveraged to bridge service delivery gaps and improve coverage in remote or resource-constrained regions.

Despite notable progress, significant implementation gaps remain. Many Member States continue to face fiscal constraints, inadequate data systems, and sociopolitical barriers to equitable coverage. Bridging these divides will require more than financial investment – it demands integrated policy design, community engagement, and institutional accountability. WHO’s role moving forward is not only to provide normative guidance but also to support countries through technical assistance, capacity-building, and cross-regional learning to ensure that no one is left behind.

V. Key Terms

Catastrophic Health Expenditure: out-of-pocket health spending that exceeds 10% of household income or 40% of non-subsistence spending

Equity in Health: the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among populations or groups

Financial Protection: mechanisms that shield individuals from catastrophic health expenditures

Health System Strengthening (HSS): integrated improvements to governance, financing, workforce, and service delivery that sustain long-term access and quality

Primary Health Care (PHC): essential, community-based care that forms the first level of contact within the health system

Universal Health Coverage (UHC): the assurance that all individuals and communities receive the health services they need without suffering financial hardship.

-

(1) What financing strategies can governments adopt to sustainably expand health coverage while reducing dependence on out-of-pocket payments?

(2) How can WHO support Member States in integrating vertical programs into unified, resilient health systems?

(3) What measures are necessary to ensure equitable distribution of health workers between urban and rural regions?

(4) How can digital health technologies be scaled responsibly to enhance accessibility without deepening the digital divide?

(5) What accountability mechanisms can strengthen national governance and ensure UHC commitments are fulfilled beyond political cycles?

(6) How can global partnerships be structured to reinforce national ownership while aligning donor priorities with long-term system sustainability?

-

Afghanistan: rebuilding basic health infrastructure post-conflict; reliant on external funding

Argentina: expanding social insurance coverage amid fiscal reform

Australia: universal public health system; focus on indigenous and rural inclusion

Bangladesh: community-based PHC success model; donor partnerships for UHC

Belgium: longstanding public health coverage; advocate for EU coordination on health equity

Brazil: SUS (Sistema Único de Saúde); large-scale public health delivery model

Cambodia: developing national insurance; improving rural healthcare access

Canada: single-payer system; strong global advocate for health equity

Chile: public-private health coverage hybrid; addressing inequality in access

China: rapid expansion of insurance schemes; investment in digital health infrastructure

Colombia: mixed insurance model; ongoing reforms to reduce regional disparities

Cuba: universal, preventive, community-centered healthcare model

Denmark: fully public system; champion of global health funding and WHO support

Egypt: gradual rollout of universal insurance law; capacity challenges

Ethiopia: prioritizing PHC and health extension workers; donor-dependent funding

France: universal, government-financed system; strong WHO supporter on UHC

Germany: social health insurance pioneer; supports WHO’s financing frameworks

Ghana: National Health Insurance scheme; focus on enrollment and sustainability

India: Ayushman Bharat program expanding coverage; emphasis on digital and rural health

Indonesia: Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN); coverage expansion for informal workers

Iran: publicly financed PHC system; regional advocate for health equity

Italy: National Health Service model; supporter of multilateral cooperation

Japan: long-standing UHC; promoting “human security” approach in health diplomacy

Kenya: universal health coverage pilot countries; prioritizing service delivery reform

Mexico: expanding public insurance post-INSABI reforms; health financing challenges

Morocco: expanding national health insurance to informal workers

Nepal: community-based coverage; reliant on WHO support for implementation

Netherlands: regulated private insurance; advocate for sustainability and innovation

New Zealand: fully public system; champion of indigenous health inclusion

Nigeria: National Health Insurance Authority Act; striving for equitable coverage

Norway: fully public system; strong donor for global health initiatives

Pakistan: Sehat Sahulat Program; challenges in rural access and implementation

Peru: mixed insurance system; rural inclusion remains limited

Philippines: Universal Health Care Act (2019); decentralized implementation barriers

Rwanda: Mutuelle de Sante; recognized for a successful community insurance model

Saudi Arabia: Vision 2030 reforms; expanding public-private health partnerships

Singapore: hybrid model emphasizing personal savings and risk pooling

South Africa: National Health Insurance rollout; tackling inequality and access

South Korea: comprehensive national insurance; promotes global UHC solidarity

Sweden: tax-funded model; champion of gender and health equity

Thailand: “30 Baht Scheme”’ major success story for UHC in LMICs

United Kingdom: National Health Service; strong multilateral engagement on health systems

United States: market-driven system; discussion around affordable care and insurance expansion

Vietnam: rapidly expanding social insurance and PHC; WHO model country for coverage gains

-

I. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping global health systems in profound ways: from clinical decision-support and diagnostic imaging, to epidemiological surveillance, supply-chain logistics, and health system administration. When well governed, AI has the potential to accelerate progress toward universal health access, improve service quality, and help systems deliver more with fewer resources. However, the deployment of AI in health also brings serious ethical, legal, safety, equity, and governance concerns – ranging from opaque model behavior, biased or non-representative training data, insufficient validation in real-world settings, data-privacy vulnerabilities, to concentrated corporate power over foundational models. The crux of the challenge in this committee lies in balance: enabling beneficial innovation while ensuring that healthcare workers, systems, and patients are protected. The critical levers are not purely technological but policy-driven: procurement frameworks, data-stewardship rules, validation and certification standards, liability regimes, transparency, and monitoring. As the World Health Organization (WHO) and Member States explore pathways for regulation, the issues span both high-income and low-and middle-income countries. Delegations must consider how to create governance frameworks that are effective globally, scalable, equitable, and flexible enough to foster innovation.

II. Historical Context

The historical evolution of AI in health and its regulation is best understood as a sequence of technological advances, policy responses, and governance adaptations. In the early stages, clinical AI was largely limited to rule-based expert systems and basic statistical models: these addressed narrow tasks (e.g., triage decision-trees, simple predictive algorithms) but lacked adaptability and often froze once deployed. As health systems digitized and large datasets became available – electronic health records, medical imaging archives, genomic repositories – machine-learning approaches emerged, which could train models from data rather than hard-coded rules. These systems produced impressive results in controlled research settings and garnered enthusiasm for their potential to improve diagnoses (e.g., imaging, pathology) and streamline operations. Yet, many of these early machine-learning systems faltered when applied outside their original contexts: concerns about “dataset shift,” demographic mismatch, and performance drop-offs in diverse real-life settings became nascent.

Meanwhile, regulatory and governance frameworks began to take shape. Recognizing the promise and risks of AI in health, WHO (in 2018) joined forces with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to establish the Focus Group on Artificial Intelligence for Health (FG-AI4H). This initiative convened experts in health, regulation, ethics, and technology to develop benchmarking frameworks and to aggregate global expertise. In 2021, the WHO published its first global guidance document on “Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health,” following extensive multilateral consultations. That document outlined six core principles – such as protecting autonomy, promoting safety and public interest, transparency, accountability, inclusiveness, and sustainability. These principles reflected a growing recognition that health-AI is not merely a matter of engineering but must be embedded in rights-based, equity-oriented, globally minded frameworks.

Subsequent years saw rapid acceleration in both AI capability and regulatory response. As generative AI and large multi-modal models (LMMs) emerged – capable of ingesting text, image, audio, and structured health data and producing similar or new modalities of output – the pace of innovation outstripped many regulatory frameworks. At the same time, major regional regulatory frameworks emerged: the Artificial Intelligence Act of the European Union (EU) classifies health-related AI as “high-risk” and imposes rigorous conformity assessment. More recently, WHO launched the Global Initiative on Artificial Intelligence for Health (GI-AI4H) together with ITU and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), building a long-term institutional structure to support country-level capacity and shared benchmarking. In March 2025, the WHO announced a new collaborating center on AI for health governance, signaling a maturation of institutional infrastructure.

The historical arc has moved from narrow pilot systems to large-scale machine-learning, then to foundation models with broad applicability, and from minimal regulation to globally oriented normative guidance, regional statutory frameworks, and institutional infrastructure. This evolution underscores both how far the technology has come and how much governance still must catch up. For many countries – particularly low- and middle-income nations – the challenge remains not only to adopt safe systems but to build the regulatory, institutional, and data-infrastructure backbone that supports responsible AI deployment. This historical background sets the stage for evaluating current governance challenges and potential solutions.

III. Current Challenges

As artificial intelligence becomes increasingly integrated into global health systems, the world faces a series of unprecedented governance, ethical, and operational challenges. The rapid evolution of these technologies has outpaced the ability of regulators and institutions to respond cohesively. While AI holds immense promise for improving efficiency, accuracy, and accessibility in healthcare, its misuse – or even its uninformed use – poses substantial risks to patient safety, privacy, and equity. The complexity of this issue lies in the balance between innovation and oversight: policymakers must ensure that technological progress does not come at the expense of human rights, transparency, or public trust. The following challenges capture the most crucial concerns facing the WHO and its Member States today:

Safety, Validation, and Generalizability: Models validated on curated datasets frequently fail when applied in different populations, clinical pathways, or infrastructures. There is no universally accepted standard for clinical validation of AI systems, external benchmarking, or post-market surveillance.

Algorithmic Bias and Health Equity: AI systems trained on datasets that under-represent certain populations (by ethnicity, geography, socioeconomic status, age, or gender) risk amplifying health disparities. Deploying such systems without local recalibration can exacerbate outcomes for the most vulnerable populations.

Transparency, Explainability, and Trust: Clinicians and patients need an understandable rationale for AI recommendations. Black-box models, closed proprietary architectures, and opaque update procedures undermine trust, complicating informed consent, clinical responsibility, and accountability.

Data Governance, Privacy, and Cross-Border Data Flows: Protecting sensitive health data used for training and inference is essential. Many low- and middle-income countries lack strong data-protection regimes or digital infrastructure to control data flows, raising risks of exploitation, re-identification, and data-sovereignty loss.

Liability and Clinical Responsibility: Existing medical-liability frameworks do not clearly cover AI systems that learn and change post-deployment. Determining who is accountable – developer, vendor, health institution, clinician – when an AI-supported decision causes harm remains contested.

Regulatory Fragmentation and Market Dynamics: A patchwork of national and regional rules (e.g., EU, U.S., Japan, China) creates inconsistent obligations – mandatory conformity assessments in some, voluntary codes in others – complicating multinational procurement, scale-up, and equitable access.

Dual-Use, Misinformation, and Generative Risks: Generative models can produce plausible but false clinical content, enabling misinformation, fraudulent telemedicine interactions, or unsafe “advice.” These concerns heighten the risk of harm and undermine trust in health-AI broadly.

Capacity Gaps and Digital Infrastructure: Even where governance frameworks exist, many health systems lack the technical capacity, regulatory expertise, or financial resources to independently evaluate models, perform monitoring, or sustain post-market surveillance – leading to dependency on commercial vendors and external validation.

These challenges reveal that AI in health is not simply a matter of technological deployment but of systemic readiness. Without comprehensive governance frameworks, inclusive data practices, and accessible infrastructure, the potential of AI to improve health outcomes could instead deepen existing global inequities. For WHO Member States, the current task is not only to regulate AI but to ensure that regulation is equitable, enforceable, and responsive to the realities of diverse health systems.

IV. Current Solutions & UN Resolutions

Recognizing the complexity of these issues, the international community – led by the World Health Organization and its partners – has begun to articulate frameworks and policies that address the governance of AI in health. These efforts aim to establish guiding principles, harmonize national regulations, and foster global capacity-building for equitable implementation. The following section outlines the key solutions and institutional responses that currently form the backbone of international efforts to regulate AI safely, ethically, and effectively across borders:

WHO Normative Guidance: In 2021, WHO published Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health, providing six core principles for health-AI and recommending accountability mechanisms for stakeholders in public and private sectors. In October 2023, the WHO issued a publication on regulatory considerations for AI in health, emphasizing safety, effectiveness, and stakeholder dialogue. In January 2024, the WHO released governance guidelines for large multi-modal models (LMMs) in health, reflecting the latest technological evolution.

Regional Regulatory Frameworks: The EU Act is an exemplar of a risk-based regulation, classifying health-related AI as “high-risk” and mandating conformity assessment and documentation. The approach is likely to influence non-EU jurisdictions and global procurement practices.

Standards and Technical Tools: Standards bodies (ISO/IEC) and research consortia are working on benchmark datasets, validation frameworks (FUTURE-AI), and reporting standards (e.g., TRIPOD-AI).

Institutional Capacity Building and International Cooperation: The Global Initiative on Artificial Intelligence for Health (GI-AI4H), launched in July 2023 by WHO/ITU/WIPO, helps Member States build governance capability, share best-practice tools, and pilot federated learning and model benchmarking. WHO’s announcement in March 2025 of a new collaborating center on AI for health governance further reflects the institutionalism of governance.

Documentation and Transparency Initiative: There is growing emphasis on public registries of deployed clinical AI, mandatory model documentation (model cards, datasheets), and pre-market/post-market surveillance of adaptive AI systems. This transparency supports accountability, oversight, and trust.

Procurement and Funding Policies for Equitable Access: Some high-income countries and global health donors are exploring public-interest AI tools and procurement frameworks that prioritize open, validated systems accessible to low- and middle-income countries, thereby reducing the access gap and avoiding dependence on a few commercial vendors.

While these initiatives mark substantial progress, they are only the beginning of a long-term process of harmonizing global governance for AI in health. The absence of a unified, enforceable framework continues to hinder consistent implementation and accountability. Moving forward, WHO must serve as both a convener and a standard-setter – bridging regional approaches, supporting capacity development, and ensuring that all Member States have access to the tools, resources, and knowledge necessary to implement AI safely and ethically. The path toward effective regulation will require not only technical guidance but also political will, multilateral cooperation, and sustained investment in health governance.

V. Key Terms

Artificial Intelligence (AI): computational methods that perform tasks normally requiring human intelligence – learning from data, pattern recognition, natural language processing, planning, and decision-making

High-Risk AI (in health): an AI system whose failure or misbehavior could lead to significant harm (e.g., diagnosis assistance, treatment recommendation) and which therefore triggers heightened conformity assessment requirements under risk-based regulatory frameworks

Large Language Model (LLM): a model trained on very large text corpora, capable of generating natural language and performing tasks based on prompts; notable for both utility and risk of “hallucinations”

Large Multi-Modal Model (LMM): an AI model that accepts and generates across multiple data types (e.g., text, image, audio, structured data) and is increasingly relevant in clinical diagnostics and multimodal health-data settings

Machine Learning (ML): a subset of AI that trains models from data to perform prediction or classification tasks rather than relying solely on hand-coded rules

Model Card/Datasheet: standardized documentation describing an AI model’s intended use, training data provenance, performance metrics, known limitations, and bias characteristics – a transparency tool recommended by technical and ethical guidance

Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP): a regulatory mechanism detailing how an AI/ML-based system may evolve post-deployment (via updates or retraining) while maintaining safety/effectiveness

Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): software intended for medical purposes without being embedded in hardware; regulatory category used for AI/ML-enabled health applications

-

● How can the aid industry and aid programs be altered to be more effective?

● What solutions exist in the case of corrupt governments keeping aid from reaching the intended communities?

● When considering how to promote pro-aid policies, what evidence and arguments can be used to counter critiques of aid?

● Every country is different; what may work in one country may not work in another. How can aid programs successfully respond to this fact?

● How can donor countries ensure they truly understand the needs and contextual information of recipient countries that may be across the world from the donor country?

● All in all, how can the international community meet the moment in the context of economic aid today?

-

The system may be broken to the point that developing nations are just getting money thrown at them by donors with various motivations, with little care about actual effectiveness.

However, this cannot be without remedy. The global economy is built upon the interdependence of nations, and without systemic tools and powers to support other countries’ development and well-being, our global economic system would arguably not even have a guise of a foundation of truth and mutual support to build trade and transnational economic relationships with. It is up to ECOFIN to save our modern aid system.

Do critiques of international aid’s effectiveness warrant defunding aid programs?

If so, how can countries best go about doing this to minimize economic shock or other negative transitional effects? If not, how can the international aid system be reformed to be more effective?

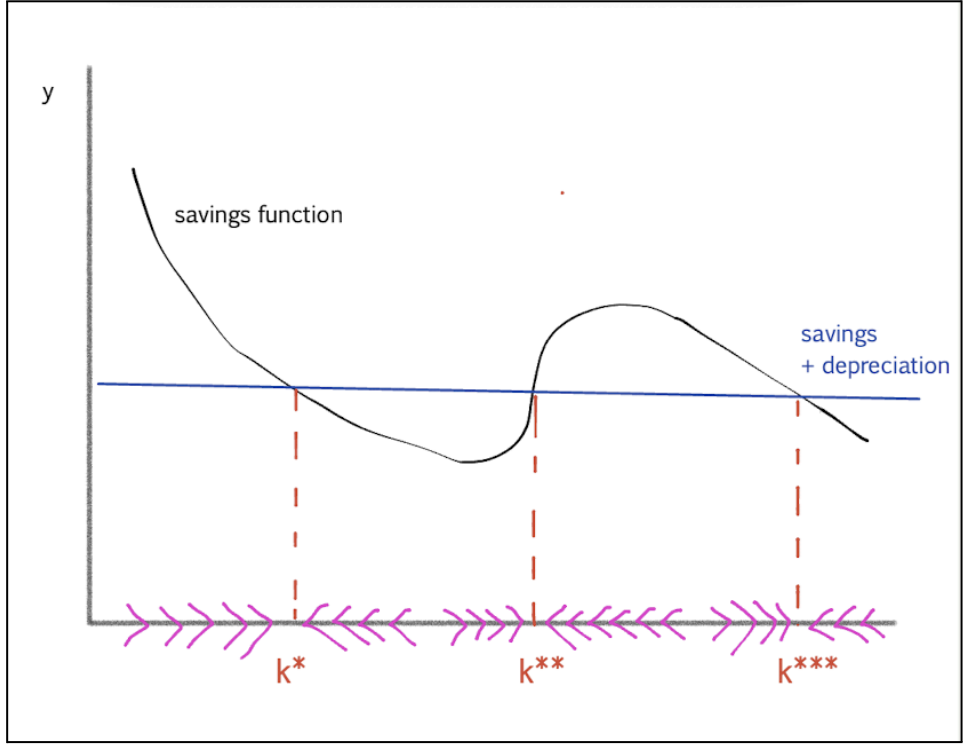

Diagram representing the economic model of multiple steady states, and the equilibrium-driven forces along the x-axis that will determine which steady state the economy will calibrate to rest at, and hence the effectiveness of aid.

Sharon Stone implores delegates at the World Economic Forum in 2005 to donate toward bed nets in Tanzania.