ECOFIN (GA)

-

Dear Delegates,

We are so excited to welcome you to CESIMS! The Secretariat has been working tirelessly to make this conference not only an enjoyable learning experience but also one that you can take with you. It will provide opportunities to develop skills, broaden your worldview, and enhance your leadership in Model UN and beyond.

My name is Kylie, I am the Under-Secretary General of Marketing for CESIMS, and I will be your chair for the Economic and Financial Committee (ECOFIN)!

I’m studying Economics and Political Science. I’m from Maine and have participated in Model UN since middle school. After graduating, I hope to contribute to the development of critical, positive, and globally minded political and economic policy.

I like running and spending time outside. My favorite books include “Wuthering Heights” by Emily Brontë, basically anything by Virginia Woolf, and “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel García Márquez.

In this committee, you all have the opportunity to engage critically with issues of international development aid, labor rights, and how countries can work together to intentionally transition to a more sustainable, equitable, and developing global economy. In addressing issues such as aid in the global economy, I hope that you all get a more well-rounded view of how international organizations can take effective steps to mediate meaningful and lasting economic change, and also get a sense of what their limitations may be.

I recommend using this guide as an initial step to independent research. This guide doesn’t provide an exhaustive look at international aid and labor practices, and further research into the topics and your country’s specific policies will prove useful.

If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out! The rest of Secretariat and I welcome you to CESIMS, and look forward to meeting you!

Sincerely,

Kylie Thibodeau

-

Code of Conduct

All delegates will be held to a high standard of behavior and will be expected to treat each other and the topics of debate with respect. No harassment or bullying of any kind will be tolerated. Sensitive discussion of topics is expected to be conducted respectfully and intelligently. The Secretary-General of CESIMS reserves the right to remove a delegate from the conference at any point in time.

Attire

All delegates will be expected to wear Western Business Attire.

Language

The working and official language of the committee shall be English.

Parliamentary Procedure

Points

There are four types of points that a delegate may raise.

Point of Order

A Point of Order may not interrupt a speaker and can be raised when the delegate believes the rules of procedure have been violated. The chair will stop the proceedings of the committee and ask the delegate to provide warranted arguments as to which rules of procedure have been violated.

Point of Personal Privilege

A Point of Personal Privilege may be raised when a delegate’s ability to participate in debate is impaired for any physical or logistical reason (for instance, if the speaker is not audible). This point may interrupt a speech, and the dais will immediately try to resolve the difficulty.

Point of Parliamentary Inquiry

This point may be raised by a delegate who wishes to clarify any rule of procedure with the Chair. It may not interrupt a speaker, and a delegate rising to this point may not make any substantive statements or arguments.

Point of Information

As the name suggests, this point may be raised by a delegate to bring substantive information to the notice. It may not interrupt a speaker and must contain only a statement of some new fact that may have relevance to debate. Arguments and analyses may not be made by delegates rising to this point. A point of information may also be used to ask questions of a speaker on the general speakers list.

Motions

Motions control the flow of debate. A delegate may raise a motion when the chair opens the floor for points or motions. Motions require a vote to pass. Procedural motions, unless mentioned otherwise, require a simple majority to pass.

Motion for Moderated Caucus

This motion begins a moderated caucus and must specify the topic, the time per speaker, and the total time for the proposed caucus.

Motion for an Unmoderated Caucus

This motion moves the committee into unmoderated caucus, during which lobbying and drafting of resolutions may take place. It must specify the duration of the caucus.

Motion to Suspend Debate

This motion suspends debate for a stipulated amount of time.

Motion to Adjourn

This motion brings the committee’s deliberation to an end, and it is only admissible when suggested by the Chair.

Motion to Introduce Documents

A successful motion to introduce essentially puts the document on the floor to be debated by the committee. The sponsor of the document will be asked to read the document and then, if deemed appropriate, the Chair will entertain a moderated caucus on the topic.

Motion to Divide the Question

This motion may be moved by a delegate to split a document into its component clauses for the purpose of voting. This may be done when a delegate feels that there is significant support for some clauses of the document, but not for the complete document.

Motion for a Roll Call Vote

A delegate may move to have the vote conducted in alphabetical order.

Motion for Speakers For and Against

If it would help the proceedings of the committee, a delegate may motion for speakers for and against a document.

Documents

Committee Documents represent the product of the committee’s deliberations and their collective decisions.

Directives

Directives are similar to resolutions in traditional committees, with the notable exception that they do not include preambulatory clauses and are much shorter and more concise. Directives are generally written in response to a specific crisis update, and can be as short as two or three clauses. All direct actions by the committee as a whole require a directive.

Communiqués

Communiqués are formal communications (private by default) directed from the committee to other governments, individuals, or organizations. Committee communiqués pass by simple majority.

Press Release

Press releases express the sentiments of the committee (NOT individuals) on any issue. They require a simple majority to pass.

Amendments

After the first draft of a committee document has been introduced, delegates may move to amend clauses of the draft. If the amendment is supported by all the sponsors of the documents, it passes as a friendly amendment.

Communication During Committee

Communication during committee may take place through handwritten notes:

Notes Between Delegates

Delegates should feel free to write personal notes to their fellow committee members. We ask that these notes pertain to the business of the committee.

Notes to the Dais

Delegates may also write to the Chair with questions regarding procedural issues of the committee, as well as a wide range of personal inquiries. Delegates should feel free to write to the Chair on any issue that would improve the committee experience. This could range from a clarification of procedural issues to substantive matters.

Crisis Notes

Crisis notes are notes written in character to fictional confidants. Backroom staffers will respond to these notes in character. The success of your notes depends on how well the notes are written and researched, and how reasonable the request is.

-

The Economic and Financial Committee (Second Committee) of the United Nations (ECONFIN) is responsible for dealing with questions about economics, global finance, and growth and development around the world. It was created alongside the other major General Assembly bodies of the United Nations during its founding in 1945 and is considered a critical part of the UN.

ECOFIN is composed of all 193 member states of the United Nations, and each of them has equal voting power. It can be described as the policymaking body for economics, global finance, and economic growth.

The topic under discussion for ECONFIN is: Meeting the Moment of Modern

International Development Aid

This topic is critical to today’s international economy; ECOFIN has not only a license but a responsibility to address this issue with consideration of the multiple perspectives and elements present.

This topic is also a complex one, as are many topics in the field of economics and diplomacy. I urge you to fight against the natural urge to simplify or make generalizing statements, and instead explore those complicating factors. If you are able to have a thorough debate that considers multiple perspectives and angles, the resolutions to come out of ECOFIN will be effective and rigorous— and hopefully propose solutions that change the international aid situation for the better.

Meeting the Moment of Modern International Development Aid

Introduction: On the State of International Development Aid

The history of global development aid is made entirely of inflection points.

Periodically, global aid faces critical demands of reform and finds it must transform to survive. The public opinion on aid, as well as the policy intentions of aid, is constantly shifting. You can take post-WW2 as an example. The Marshall Plan provided billions in economic assistance to Western European countries to attempt to rebuild their economies and prevent them from falling to communism. Public opinion is hard to reliably measure, but aid in this form in this moment generally saw public support.

Then, aid in the 2000s shifted in some ways toward larger-scale nation-building purposes, like American aid toward Afghanistan. Again, public opinion is hard to measure, but the American public’s support for this form and form of aid is arguably low.

In response to continually shifting aid priorities and levels of support, donor countries usually restructure their aid agencies, adjust their budgets, and may even lobby for creating or abolishing specific UN initiatives. Typically, once the aid industry adjusts to the whims of donor countries, an aid crisis is averted and business continues as usual. However, we do not know if the modern situation will continue to reflect this pattern.

Today, a primary critical force in the global aid industry is the United States’ Trump administration’s second term. USAID, the world’s largest development agency, has been gutted, losing 86% of its programs, shutting down its headquarters, and terminating nearly all of its employees. For many, this is a concerning development. It is estimated that in 2023, USAID contributed to nearly $43.8 billion in aid, about three of every five foreign-assistance dollars.

Aid offers support and resources to countries and people who may otherwise be left behind; it is the world’s most central attempt to create equality and economic development in a globalized world.

How can the international community work to defend international aid in the midst of such destructive action against the international aid system?

-

There are arguments to be made regarding the effectiveness of international aid.

These arguments have led us to the poor state of support for aid we have found ourselves in. Popular critiques of international aid include:

1. We aren't giving large enough amounts of aid to make a difference.

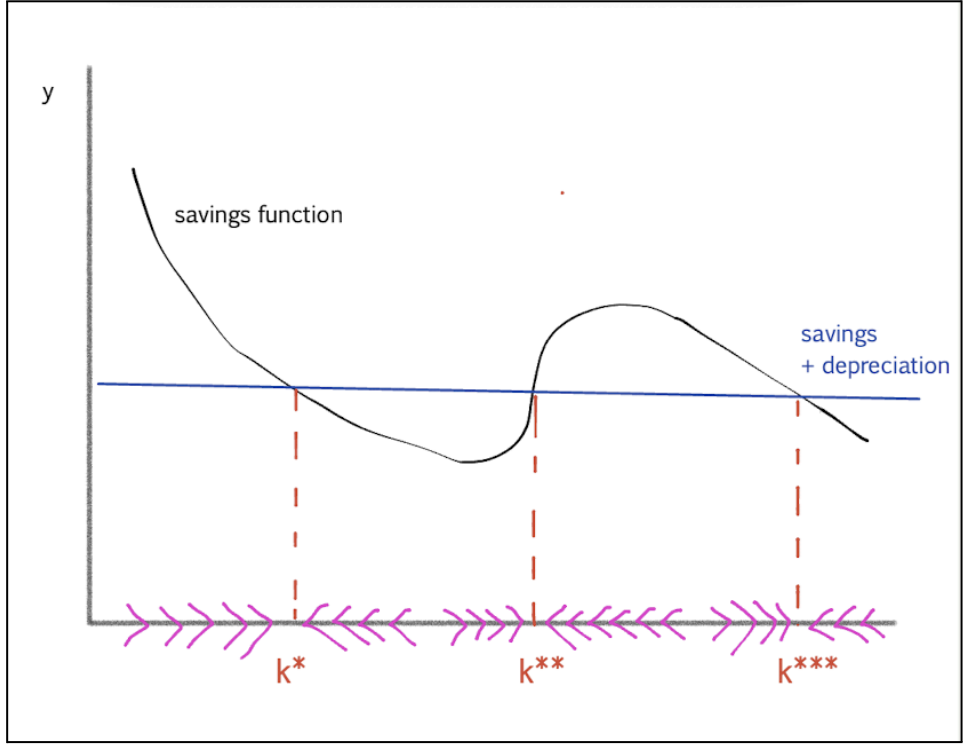

Some macroeconomists subscribe to the idea of “steady states,” which are places where the growth of an economy is equal to 0 (meaning there is no long-term sustained growth). This is a form of “equilibrium,” specifically regarding an economy’s long-term growth; This is theoretically where a country’s economy will rest. However, a country can have multiple steady states, each with no long-term sustained growth, but with different levels of steady capital (k).

The theory is that aid needs to be large enough to push an economy’s growth to the next steady state, which finds equilibrium and therefore is able to sustain at a higher level of capital. See the diagram at the bottom of this webpage.

In the diagram (see below), k* represents the first steady state, k** the second, and so on. In the situation described in the diagram, aid could potentially push a country’s economy past k*

and toward a higher steady state like k***, where capital rests at a higher level,

theoretically making the economy better off. This is the most graphical/mathematical

this committee will get, I promise. (Unless you guys want to make it more

math-y/macroeconomic-y in committee, that’s your prerogative.)

Final note: this diagram is a simplified version of what is already an economic

model (meaning not truly representative of the real-world economic situation—

especially concerning k**), so there are complexities to this that exist that may be

beyond the scope of this committee, but you can feel free to research and use it on your

own.

2. Aid just doesn't work inherently and systemically.

The aid industry is not subject to the same natural market forces of demand and supply that naturally competitive markets are. In competitive markets, producers must respond to the demand of consumers if they can expect to make a profit at all (in other words, the rational producer will only produce what consumers will actually buy— there is no profit in an unwanted good). However, aid does not follow the conventional market dynamic of supply meeting demand under profit- and utility-driven decision-making. This means there is no accountability for the producers (in the aid industry, this is the donors) to actually produce what consumers (in the aid industry, this is the recipient countries) need.

Challenges regarding corrupt governments are also a big critique— if the governments of countries receiving aid are corrupt, the money or resources do not often actually reach the donor’s intended community because they get lost in the corruption of the receiving country’s government.

There’s also the argument that there are bureaucratic challenges. Imagine aid for Ethiopia. Aid first comes from the donors, then goes to World Bank bureaucrats, then Ethiopian bureaucrats, and only then to Ethiopian citizens. There are many places along this path where the aid could catch a hitch. In addition, it can just be a time-consuming process, which can reduce the impact of the aid.

It may also be relevant to consider how aid sometimes is not truly motivated by an incentive to truly help a country, but may be good PR for a celebrity or the government itself. For an example of the former, in 2005, Sharon Stone raised $1 million for mosquito bed nets in Tanzania (see image below).

The impromptu manner in which she raised the issue and her seemingly heartfelt motivations made the public celebrate her. Unfortunately, however, it is unknown how effective this was: The World Economic Forum does not know how many bed nets reached actual villages in Tanzania (as opposed to being stolen by corrupt border officials), how many were actually used as bed nets (as opposed to fishing nets, for instance), or how many were used correctly.

-

Case Study 1: Post-1980s Ghana

Ghana has often been cited as a highly successful aid recipient in sub-Saharan Africa. Ghana’s GDP growth began to dip in the early 1960s, and this downward spiral continued until about 1966, the time of the first coup d’etat by the military. The resurgence of growth was short-lived, however, falling substantially again in the early 1970s, exhibiting a downward trend until the early 1980s. Since then, economic growth has been higher than its historical average.

The change in the 80s has been attributed to it receiving substantial foreign aid, and combined with economic reform, liberalization, and a degree of institutional improvement.

Ghana, receiving conditional aid, saw a positive and statistically significant long-run impact on growth. Ghana’s strategy included realistic policy ownership by the government, alignment of donor support with national priorities, and improving the investment landscape.

Ghana’s poverty rate dropped from around 53% in 1991 to 21% in 2012, and HDI also rose from 0.44 in 1975 to 0.55 in 2005, compared with a rise from 0.39 to 0.50 for the Sub-Saharan Africa median over the same period.

It is important to note that many factors could be at play for this, but it is agreed upon that aid was a contributing factor.

Economic analysts say aid in Ghana saw success for multiple reasons:

● Ghana’s government implemented reforms (e.g., liberalised trade, improved management), which allowed aid to have leverage rather than simply be “given.” A system of accountability was created.

● Similarly, the relationship and understanding between donors and Ghana was strong— Ghana knew what was needed and donors effectively responded.

● Improving the quality of governance, investing in human capital, and strengthening administrative capacity helped turn aid into more than just cash transfers.

● Strategic timing & context: Aid entered at a time when Ghana’s economy was becoming more open and stable, meaning the country could absorb funds more effectively.

Although Ghana’s economic well-being arguably improved, many challenges remain in inequality, institutional capacity, and economic diversification. However, Ghana’s case still illustrates how foreign aid can support development, if combined with domestic reform, alignment, and institutional capacity. It also shows that aid effectiveness depends heavily on the recipient’s context rather than simply the size of the aid flow.

Case Study 2: Post-2001 Afghanistan

Afghanistan received large volumes of foreign assistance (especially from the United States) over many years, particularly in the post-2001 era (See the table below for a breakdown of the numbers).

However, many economists argue that the outcomes were disappointing in terms of sustainable development, institutional strengthening, and long-term improvement in Afghan well-being.

Many argue that foreign aid to Afghanistan, instead of supporting economic development and increasing citizen wellbeing, “fueled corruption and failed to improve the country’s economy or human development index.”

In fact, Afghanistan’s HDI even declined in the approximate period of 2015-2021. Some interrelated issues with this aid situation include Afghanistan being too dependent on aid, not being able to effectively absorb the aid, corruption, and, in some cases, aid being captured by elites or war-economy actors. While efforts to lay the foundation for sustained economic growth were numerous, many collapsed when donor priorities shifted or security worsened; the sustainability of economic development was weak. The government of Afghanistan was too unstable to effectively create long-term economic plans.

One could make the argument that we identified earlier about aid being ineffective because we are simply not donating enough to push to the next steady state; however, the issue with that in this case is that even when large sums were delivered to Afghanistan, the local governmental systems often lacked the capacity to spend effectively or manage the economic development projects.

Lessons to be learned from this situation include:

● High volumes of aid do not guarantee effectiveness. The quality of institutions, governance, and adaptation to local conditions matter.

● For fragile or conflict-affected states with resultant weaker governments, peace and institution-building may first be required. (However, then the question of sovereignty becomes increasingly tied up in this.)

This case shows what can happen when foreign aid is deployed in a challenging environment without the right supporting conditions. It highlights the risks associated with large aid flows and the importance of institutional frameworks, governance, security, and sustainability when designing development assistance programs.

-

Emu Cabinet:

Emperor Featherplume – Supreme Leader of the Flock: As the oldest surviving emu in rural Western Australia, Featherplume is revered for leading migrations for decades. He is wise but ruthless, and carries authority among all emus. His goal is to totally eradicate fences and wheat farms, which he sees as symbols of human oppression. A charismatic, unifying leader, Featherplume commands loyalty—even to the point of suppressing opposition. Given his age, Featherplume is often stuck in his ways, which creates conflict with younger members of the flock.

General Beakbreaker – Minister of Defense: Beakbreaker has fought her fair share of conflicts with farmers’ weapons, as shown by the large scar across her face. She is fierce, hot-headed, and thrives on direct confrontation—qualities that shape her war strategy. Her favored method of war is open-field charges. While risky, she finds them exhilarating and has a special talent for remaining safe from bullets. Beakbreaker can be a loose cannon, and while she is a great leader, her physical strength, mental prowess, and ambition threaten other members of the flock who hold power.

Comrade Talonclaw – Minister for Agriculture: Talonclaw has a talent for organizing quick, efficient crop raids in Western Australia. He is a practical, hardworking bird who hates humans for believing they are superior beings. He finds ruining their farms and stealing their crops to be just, as humans have always treated emus as second-class citizens. His loyalty is to his flock, and his goal is to ensure every emu has enough wheat and barley to survive—even if that means breaking into humans’ farms. His organization skills allow him to manage resource distribution among flocks, giving him intimate knowledge of each individual bird which will prove useful during the war.

High Priest Longstride – Minister for Religion and Tradition: Like humans, emus have their own religions and traditions. Longstride’s job is keeper of ancient emu migration stories. He is mysterious, poetic, and believes in the great beyond. While he witnesses the deaths of many flock members during the war, he sees their physical demise on Earth as the beginning of their lives elsewhere. This perspective makes him one of the most optimistic birds in the flock, which is vital during the trying days of the war. His goal in the conflict, which he frames as a holy struggle, is to preserve sacred roaming lands.

-

● How can the aid industry and aid programs be altered to be more effective?

● What solutions exist in the case of corrupt governments keeping aid from reaching the intended communities?

● When considering how to promote pro-aid policies, what evidence and arguments can be used to counter critiques of aid?

● Every country is different; what may work in one country may not work in another. How can aid programs successfully respond to this fact?

● How can donor countries ensure they truly understand the needs and contextual information of recipient countries that may be across the world from the donor country?

● All in all, how can the international community meet the moment in the context of economic aid today?

-

The system may be broken to the point that developing nations are just getting money thrown at them by donors with various motivations, with little care about actual effectiveness.

However, this cannot be without remedy. The global economy is built upon the interdependence of nations, and without systemic tools and powers to support other countries’ development and well-being, our global economic system would arguably not even have a guise of a foundation of truth and mutual support to build trade and transnational economic relationships with. It is up to ECOFIN to save our modern aid system.

Do critiques of international aid’s effectiveness warrant defunding aid programs?

If so, how can countries best go about doing this to minimize economic shock or other negative transitional effects? If not, how can the international aid system be reformed to be more effective?

Diagram representing the economic model of multiple steady states, and the equilibrium-driven forces along the x-axis that will determine which steady state the economy will calibrate to rest at, and hence the effectiveness of aid.

Sharon Stone implores delegates at the World Economic Forum in 2005 to donate toward bed nets in Tanzania.